Student Paper Series #4/2025

This blogpost, written by two MA students as part of their final assignment for the course The Policy Cycle of the European Economic Governance, focuses on the final stage of the EU policy cycle. By examining the effectiveness, responsiveness, and fairness of European economic governance, the authors assess how EU policies perform in practice and to what extent they achieve their intended goals. Their discussion is complemented by empirical findings, which enrich their critical reflection and provide a grounded perspective on the functioning and evaluation of EU economic governance.

By Anna Stock and Samuel Prinz

Effectiveness refers to “the ability to be successful and produce the intended results” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.-a). To assess this pillar, we first need to investigate the purpose of the framework. The European Central Bank states that economic policy and subsequent economic reforms are tools to raise productivity in the euro area, strengthening the growth potential of the Euro. Moreover, they contribute to lowering price pressure, enhancing competition and fostering innovation all leading to a better adaptability in case of economic shock (European Central Bank 2025). In addition, the general aim of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which was introduced as part of the third stage of economic and monetary union, is to ensure that member states maintain sound public finances.

However, the weak enforcement of the compliance with the SGP led to serious fiscal imbalances among member states. In response, the EU’s economic governance framework was supplemented with eight regulations and one international treaty (European Union, n.d.). Nevertheless, both the European Union and the Euro area (see Figure 1) still face a serious deficit measured in percentage of GDP, even exceeding the 3% deficit which member states agreed upon as a value to trigger an excessive deficit procedure (European Council, n.d.). Although the Union seems to slowly recover after the Covid-19 pandemic, the growth curve pointing towards no deficit is very shallow.

As for the goal of strengthening the growth potential of the Euro, the data mirrors trends from the budget deficit/surplus. Euro area and EU countries behave similarly, first showing a slow growth of GDP rate, before dropping during the Covid-19 pandemic, sharply increasing only to be haunted by the next recession starting 2021.

Regarding productivity, all indicators show a steady growth (disregarding the pandemic), except for real labor productivity per person, which follows a long downward trend. Although the growth experienced a slight disruption in 2024, most indicators are still at pre-pandemic level at the end of 2024.

Through the European Semester, member states also receive country specific recommendations based on the assessment of macroeconomic developments in the respective country (Helmdag and Väänänen 2024). Therefore, “the ability to produce a successful result” should also imply that countries conform to these recommendations. However, in 2019, in almost 2/3 country specific recommendations were not implemented (no or limited progress, 60.2%) and only 1.1% saw full or substantial progress, while in 38.7% some action was taken (Angerer, Grigaitė, and Turcu 2020). Nevertheless, the excessive deficit procedure has on average delivered the expected outcome (Franchino and Mariotto 2025) and has been an important driver for fiscal policies in the euro zone area in the post-2009 period (De Jong and Gilbert 2020).

Policy responsiveness implies that “government action responds to the preferences of its citizens”. It is, however, different from mere representation which posits that government mirrors the preferences of public opinion (Erikson 2013). At the very core of this debate stands whether the public even has a set of coherent opinions or attitudes or whether they are imposed by the elite. Following McGuire (1989, 50) who credits structure to citizens attitudes saying they are better organized “than a bowl of cornflakes”, we investigate how the economic policy of the European Union is received by its citizens.

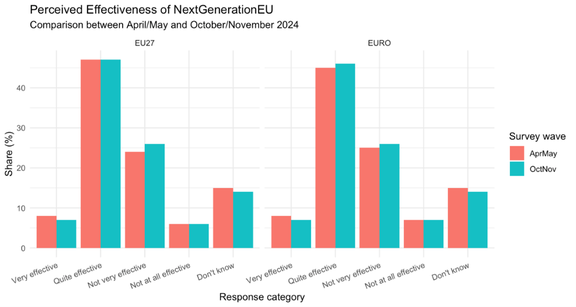

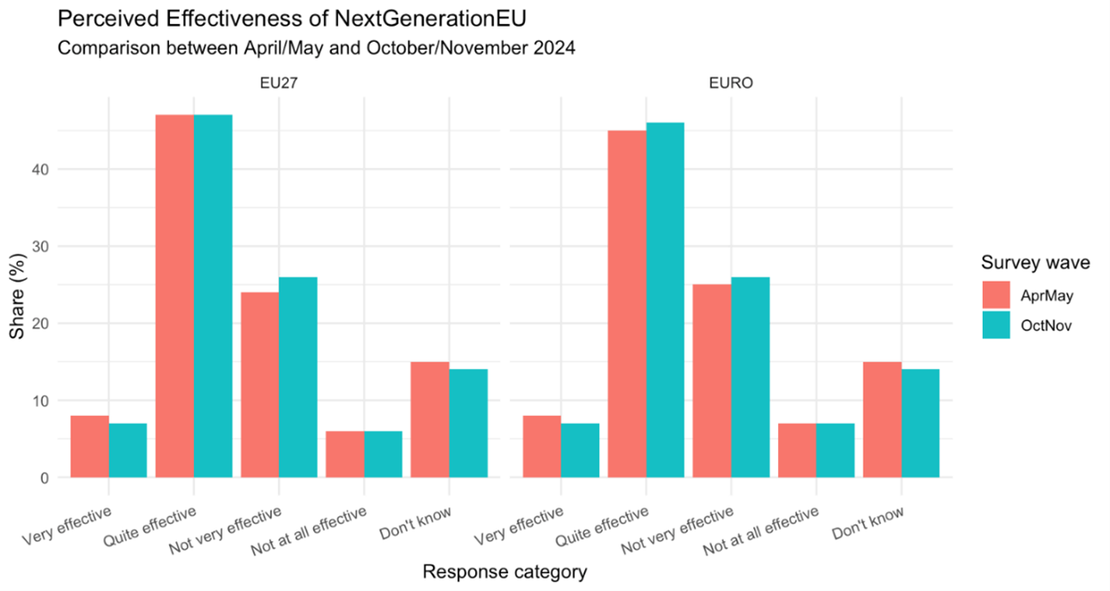

While public support for debt reduction is not significantly influenced by European supranational fiscal rules, which suggests that abstract commitments to EU rules are not enough to persuade the public when it comes to areas where costs are high (Aspide 2024), the EU citizens are relatively supportive of EU economic policy instruments. The NextGenerationEU was put in place as a temporary recovery instrument to support the transition into a greener, more digital, more resilient future following the Covid-19 pandemic (European Commission, n.d.-b). Figure 4 is based on the autumn 2024 Standard Eurobarometer and shows that the overall majority of respondents rate NextGenerationEU as quite effective.

However, the public should not be seen as one homogenous group – socio-economic indicators matter. According to Eurobarometer data, fiscal integration is more supported by owners of financial assets and individuals with higher incomes, both of whom are more supportive of financial help for other member states and authority transfer in line with fiscal coordination to the EU (Daniele and Geys 2015). Regarding EU-bonds, which are the main funding instrument of the European Commission uses under its unified funding approach (European Commission, n.d.-a), individuals with high income or assets do not show more support. In contrast, respondents from countries with higher levels of public debt show more endorsement for them and Eurobarometer bailouts. Respondents form countries with high levels of social expenditure remain skeptical, ultimately out of fear that their existing welfare system might be diluted. The last two interesting indicators are trust in the EU and placement on the political spectrum. Individuals that exhibit more trust in European institutions are more likely to support fiscal integration. Furthermore, extreme political positions lead to significantly more support of Eurobonds; with individuals more on the left more open for financial aid to other member states, mirroring preferences of left- vs. right-wing parties. (Daniele and Geys 2015).

Finally, this blog post evaluates the fairness of EU economic policy. Fairness refers to “the quality of treating people equally of in a way that is right of reasonable” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.-b). In the sense of the European Union economic policy, this means that no member state should receive a disproportionate number of benefits from a given policy, be able to fend off sanctions or (in the context of the economic policy country specific recommendations or an excessive deficit procedure) not comply.

Lundgren et al. (2019) demonstrate that there are no clear losers and winners in the bargaining of the Eurozone reform. Although the bargaining success of actors is evenly distributed across member states, some differences between groups of states emerge, contradicting popular believes. Old member states do worse compared to new member states. Large member states fare worse than small member states. Eurozone members do better than non-Eurozone members and Southern member states have less success than member states in the North or the East.

Instead, the most accurate way to predict bargaining outcomes and success in EU economic governance relies on salience and actors’ powers – the compromise model (Franchino and Mariotto 2022). What depends on countries size or amount of contribution to the EU buget, however, is the toughness of recommendations. Larger countries and net constributors are able to weaken their recommendations and countries with higher vorting power were less likely to comply prior to the introduction of the European Semester (Franchino and Mariotto 2025).

Moreover, bargaining success (at least during the negotiations in the European Council’s 2010 task force on strengthening economic governance, the pre-decision stage for the Six-Pack) indicates that member states that have a position which is more distant from the Commission’s are more successful, as are member states whose position is closer to the European Central Bank, showing that the influence of expertise is important. Whether a country is a creditor or a debitor in the European context does not allow for robust conclusions. Finally, if a member state has a powerful European Affais Committee (EAC) in their national parliament, it was more powerful during negotiations (Moloney and Whitaker 2023).

Finally, one needs to consider the balance between structure and agency. In this light, the Maastricht Treaty on European monetary union is the product of underlying structural factors, among thoose the growing capital mobility, the dynamics of the single market and the assymstric functioning of the EMS. However, it was agents that transformed the system from one insitutional equilibrium (i.e. EMS) to another (i.e. EMU). At this stage, epistemic communities are a group of actors that can bolster fairness. During these negotiations central bankers emerged as a key group that was bind into the process to facilitate the national acceptance of monetary union (Kaelberer 2003), ultimalely equalizing member states.

The goal of this post war to evaluate the effectiveness, responsiveness and fairness of the EU economic policy. In short, the European Union did a decent job in its economic architecture. The newly established system doesn’t favour powerful member states and doesn’t produce clear winners or losers during the bargaining process. Furthermore, support for the newly created tools like the NextGenEU is fairly high in the general population. Still, there is room for improvement. Specifically in terms of effectiveness and increasing the compliance of country specific recommendations, the EU has to close the gap between its expectation and the current reality.

Taken together, the EU’s policy architecture remains a balancing act between rules and discretion, unity and diversity and expertise and politics. Strengthening the effectiveness, responsiveness and fairness is not only about technocratic reform but will help to maintain the democratic legitimacy of the European integration itself.

References

Angerer, Jorst, Kristina Grigaitė, and Ovidiu Turcu. 2020. “Country-Specific Recommendations: An Overview - September 2020.” European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/624404/IPOL_BRI(2018)624404_EN.pdf.

Aspide, Allessia. 2024. “The Non-Effect of European Fiscal Rules on Public Opinion - EUROPP.” EUROPP - European Politics and Policy (blog). October 10, 2024. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2024/10/10/the-non-effect-of-european-fiscal-rules-on-public-opinion/.

Cambridge Dictionary. n.d.-a. “Effectiveness.” Accessed June 12, 2025. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/effectiveness.

———. n.d.-b. “Fairness.” Accessed June 12, 2025. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/fairness.

Daniele, Gianmarco, and Benny Geys. 2015. “Public Support for European Fiscal Integration in Times of Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (5): 650–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.988639.

De Jong, Jasper F.M., and Niels D. Gilbert. 2020. “Fiscal Discipline in EMU? Testing the Effectiveness of the Excessive Deficit Procedure.” European Journal of Political Economy 61 (January):101822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.101822.

Erikson, Robert S. 2013. “Policy Responsiveness to Public Opinion.” In Political Science, by Robert S. Erikson. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199756223-0103.

European Central Bank. 2025. “Economic Policy.” 2025. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/eaec/ecopolicy/html/index.en.html.

European Commission. 2024. “New Economic Governance Framework.” 2024. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-and-fiscal-governance/eu-assessment-and-monitoring-national-economic-policies/evolution-eu-economic-governance/new-economic-governance-framework_en.

———. n.d.-a. “Funding Instruments.” Accessed June 12, 2025. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/eu-budget/eu-borrower-investor-relations/funding-instruments_en.

———. n.d.-b. “NextGenerationEU.” European Commission. Accessed June 12, 2025. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/eu-budget/eu-borrower-investor-relations/nextgenerationeu_en.

European Council. n.d. “Excessive Deficit Procedure.” Consilium. Accessed June 12, 2025. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/excessive-deficit-procedure/.

European Union. n.d. “Stability and Growth Pact.” EUR-Lex. Accessed June 12, 2025. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=legissum:stability_growth_pact.

Eurostat. 2025. “Productivity Trends Using Key National Accounts Indicators.” 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Productivity_trends_using_key_national_accounts_indicators.

Franchino, Fabio, and Camilla Mariotto. 2022. “Bargaining Outcomes and Success in EU Economic Governance Reforms.” Political Science Research and Methods 10 (2): 227–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.26.

———. 2025. Balancing Pressures: The Politics of Governing the European Economy. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Helmdag, Jan, and Niko Väänänen. 2024. “Financial Sustainability Above All Else? Drivers and Types of Pension Reform Recommendations in EU Socio‐economic Governance.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, October, jcms.13700. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13700.

Kaelberer, Matthias. 2003. “Knowledge, Power and Monetary Bargaining: Central Bankers and the Creation of Monetary Union in Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 10 (3): 365–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000085351.

Lundgren, Magnus, Stefanie Bailer, Lisa M Dellmuth, Jonas Tallberg, and Silvana Târlea. 2019. “Bargaining Success in the Reform of the Eurozone.” European Union Politics 20 (1): 65–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518811073.

McGuire, William J. 1989. “The Structure of Individual Attitudes and Attitude Systems.” In Attitude Structure and Function, edited by Anthony R. Pratkanis, Steven J. Breckler, and Anthony G. Greenwald, 37–69. The Third Ohio State University Volume on Attitudes and Persuasion. Hillsdale, NY: Erlbaum.

Moloney, David, and Richard Whitaker. 2023. “Working up the Six-Pack: Bargaining Success in the European Council’s Task Force on Strengthening Economic Governance.” European Union Politics 24 (3): 559–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165231157601.

About the Authors

Anna Stock completed her master’s degree Political Science: European and International Politics at the University of Innsbruck, where she also obtained a master’s degree in Translation Studies. As a student research assistant for the Department of Political Science and the Foreign Policy Lab, her research focuses on the citizens’ attitudes on foreign policy in small states and citizens’ attitudes on international order.

Samuel Prinz received his bachelor’s degree in Political Science at the University of Tübingen and is currently enrolled in the master’s programme Political Science at the University of Innsbruck, focusing on European politics.

How to Cite

Stock, Anna/Prinz, Samuel (2025): Effectiveness, Responsiveness and Fairness of the EU Economic Policy, Powi Blog, Institut für Politikwissenschaft, Universität Innsbruck, https://www.uibk.ac.at/de/politikwissenschaft/kommunikation/powi-blog/prinz-stock-eu.

This article gives the views of the author(s), and not necessarily the position of the Department of Political Science.

The text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).