Blog: Project Updates

It was a productive summer for our project and we are happy to share that more research has been published. Over the past months, our project team has published several new studies. In this blog, we highlight three publications that focus on how governments assign blame across borders and how citizens respond to different crisis communicators online.

How governments blame each other

In this publication, we examine the strategic role of blame. In this article, Christian Schwaderer, Sarah C. Dingler, Lore Hayek and Martin Senn investigate how governments assign responsibility to other states during crises. Looking into press conferences from 18 countries, the study shows that factors such as crisis severity, geographic proximity as well as political and cultural proximity shape the likelihood of cross-border blaming. Countries particularly visible during the early pandemic such as Italy and China were more frequently blamed. This work highlights how governments strategically navigate international narratives, especially under pressure.

Read the full paper “Inter-state blaming during crises: the role of non-institutional factors”, published in the Journal of European Public Policy here: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2025.2566998

How citizens respond to government communicators online

Another line of research in our project focuses on how citizens react to government communication during the pandemic and how closely conversations align with what governments communicate. Two newly published articles by Christian Schwaderer examine these dynamics from different angles. Both studies draw on our press conference data but extend it with large-scale social media datasets. The first examines tweets and shows that public responses vary substantially depending on who communicates: experts are generally more positively evaluated than political actors, and women communicators receive more positive reactions, particularly in more intense crisis phases.

The second study explores whether and when public conversations mirror the content of government messaging. It finds that massage characteristics, such as tone and complexity, shape the degree of convergence between official communication and online discourse. Together, these articles shed light on how government messages reason in hybrid media environments.

Read the articles here:

“Whom to Trust in Crises? The Influence of Communicator Characteristics in Governmental Crisis Communication”, published in Media and Communication: https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.10425

“When Crisis Conversations Converge: Linking Government Messaging and Online Responses during Covid-19”, published in Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy: https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.70042

Over the past months, our project team has been busy turning our research and analyzes into concrete output. Many of our papers have progressed from drafts and conference presentations to full publications. This is a fitting moment to take stock and share an overview of what has recently appeared in print.

What stands out across these publications is the breadth of what we have been able to examine: How governments communicate, who communicates, how the media picked up the messages, and how citizens react during crises. The studies build on our government press conference data and combine it with additional material such as newspaper articles and comparative country information, allowing each contribution to highlight different dimensions of crisis communication.

How the media responded to government communication

The first of these publications comes from Lore Hayek, who examined how newspapers framed government press conferences during COVID-19. Her analysis shows that while some newspapers echoed government messaging more positively, others were more skeptical, and this varied considerably between countries and between newspaper types. Press conferences clearly shaped media agendas, but the tone and emphasis differed.

Read the full paper “Media Framing of Government Crisis Communication During Covid-19”, published in Media and Communication here: https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.7774

Who actually speaks for the government?

In another publication, Lore Hayek, Sarah C. Dingler and Martin Senn turn to the question of who takes the stage during moments of crisis. Their findings show that heads of government are especially visible when key decisions are announced, but not necessarily when crises escalate. Leadership presence seems to follow strategic considerations more than real-time crisis dynamics. This work adds an important perspective on the choreography of political communication in volatile times.

Read the full paper “Who Gets to Speak When the Rook Is on Fire? Leadership in Political Crisis Communication”, published in Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy here: https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.70012

How governments establish authority through rhetoric

Focusing further on the leadership during crises, Martin Senn, Christian Schwaderer, Lore Hayek and Sarah C. Dingler explore the rhetorical building blocks that governments rely on to create authority and guide public perception. Across then countries, the paper identifies four recurring rhetorical styles, ranging from information-oriented approaches to leadership-oriented, action-oriented or awareness-oriented styles. Governments draw on these styles in different ways, and the article provides a large-scale attempt to map these patterns systematically.

Read the full paper “Mapping rhetorical styles in political crisis communication”, published in Policy Studies here: https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2025.2546385

From April to June 2025, the PhD researcher working within our project, Christian Schwaderer, spent a research stay at the Department of Journalism, Media and Communication (JMG) at the University of Gothenburg. The stay offered a welcome opportunity to exchange ideas with scholars approaching crisis and political communication from different perspectives.

During his visit, Christian presented several elements of our ongoing work. He introduced project papers focusing on how governments strategically use blame in their crisis communication, a topic that received interesting discussions about responsibility, public perception and insights into this phenomenon in Sweden. These conversations brought new angles into the project, and we will share more on these papers in upcoming blog posts.

Christian also discussed parts of his dissertation, presenting work that is currently being developed into articles as well as the broader framework of the thesis. The feedback he received at JMG helped a lot in finalising individual papers and the conceptual structure of the dissertation. He also had the opportunity to hold a guest lecture in the master’s programme, where he discussed crisis communication together with the students. Overall, the stay provided a chance to connect with the PhD community at JMG and exchange views on crisis and political communication research, methods, and academic life more generally.

We would like to thank everyone at JMG for the thoughtful discussions and the warm welcome during Christian’s visit. The insights gained over these months are already reflected in ongoing work within the project, and we look forward to future exchange.

We are happy to see our paper „Everyone will know someone who died of Corona: Government threat language during the COVID-19 pandemic“ out now in the European Journal of Political Research. The publication marks an important milestone for our project: it is the first article based on the unique dataset of government press conferences we collected across 17 OECD countries and three U.S. states. Read the article here:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12676

In the paper, we examine how governments made use of threat language during the initial phase of the pandemic, an element of crisis communication that can help increase public awareness and compliance but can also backfire if overused. Using more that 1,100 press conferences, we show that threat language was not random but followed patterns. One of our key findings is that the subject area matters much more than who is speaking. Threat appeals were especially likely when governments addressed issues related to the health system or public management, reflecting the central pressures on hospitals, medical infrastructure, and administrative capacities in early 2020.

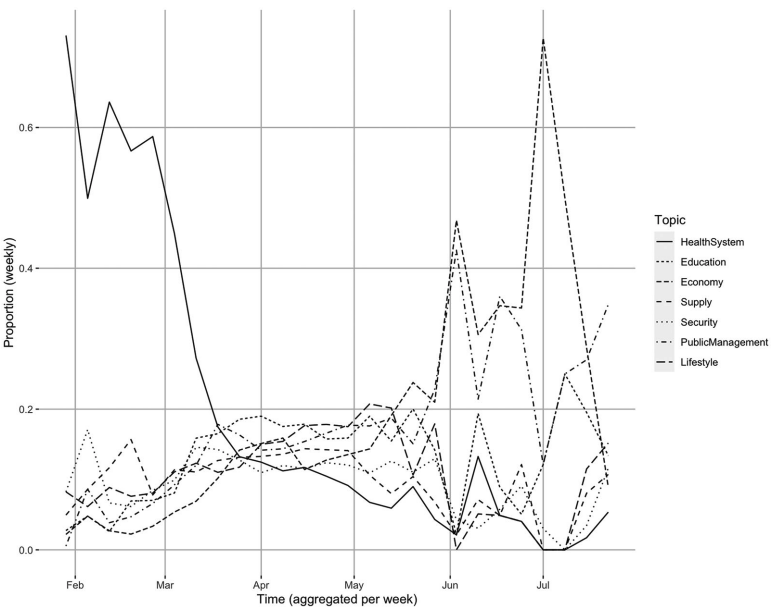

We also find gender differences in the use of threat language. While speakers in different roles used threat language at similar rates, men were more likely to employ it that women, a result that fits broader research in gendered communication styles. As government communication shifted over time from an almost exclusive focus on health issues to disruptions of daily life, education, and the economy, the diversity of threats expanded, reflecting the pandemic’s multi-dimensional nature, as shown in Figure 1.

Overall, our results suggest that crisis communication across countries became more similar that previously assumed: when facing a comparable challenge, governments tended to converge in how they communicated risks and dangers. We are happy that this research is now published and hope it. Contributes to a better understanding of how governments navigate the balance of informing the public and avoiding unintended fear during crises. More publications will follow soon!

We were excited to present an updated version of our paper at the “Tag der Politikwissenschaft 2022”, hosted by the University of Graz, Austria. This event - roughly translated as “Day of Political Science” - was intended to serve as a forum for the discussion of current research work and contribute to stronger nationwide networking between experienced researchers and young scholars.

Our paper, titled "What should we be afraid of? - Threat narratives in government crisis communication during COVID-19", explores televised press conferences as instruments of political crisis communication. Specifically, we concern ourselves with the factors influencing the intensity and nature of threat appeals, their frequency of usage and their specific utilization in the crisis communication of governments during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. We draw on a unique dataset - translated transcripts of televised speeches and press conferences by national/state governments held by heads of government and states in 17 OECD countries and three U.S. states - collected during the first phase of the pandemic in early 2020. Additionally, we collected secondary data regarding biographical information on the speakers, the epidemiological situation and the respective political system. We then utilize different approaches of automated text analysis to identify rhetorical strategies and show how governments and heads of state adapt crisis communication over the course of the pandemic. Our paper contributes to the existing literature on crisis communication and the political fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic by comparatively examining government crisis responses, and it also has implications for future crises.We are able to not only show remarkably similar political crisis communication across countries, but additionally concluded several important differences in crisis communication regarding the use of threat narratives across topical, temporal and gender dimensions.

The “Tag der Politikwissenschaft 2022” was a great opportunity to receive further feedback on our research, as well as to network with other early-career researchers from across the nation. Thank you again to the University of Graz and the Austrian Society for Political Science for the successful hosting of the event. We are already looking forward to next year’s D-A-CH convention at the Johannes-Kepler-Universität in Linz: https://www.oegpw.at/oegpw-konferenzen.

We are excited to present our paper at the ECPR conference in Innsbruck, Austria in August 2022. The conference is one of the most prestigious events in the field of political communication research, and we are honored to have the opportunity to showcase our research to an international audience of scholars and practitioners. Since our university is also hosting the event, the coming days are most definitely going to be eventful.

Our paper is titled "What should we be afraid of? - Threat narratives in government crisis communication during COVID-19", and it explores televised press conferences as instruments of political crisis communication. We argue that a country’s political system, the course of the pandemic, and the state of a country’s national health system systematically impact the ways in which threats - e.g. to (individual or collective) health, the economy, security, or liberty - are constituted in governments’ crisis communication. We draw on a unique dataset of 1013 press conferences held by heads of government and states in 17 OECD countries in the first phase of the pandemic in early 2020 and utilize different approaches of automated text analysis to identify rhetorical strategies and show how governments and heads of state adapt crisis communication over the course of the pandemic. Our paper contributes to the existing literature on crisis communication and the political fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic by comparatively examining government crisis responses, and it also has implications for future crises.

The ECPR conference is a great platform for us to receive feedback on our paper from experts in the field, as well as to network with other researchers who share similar interests and goals. We are looking forward to engaging in fruitful discussions and hearing about the latest developments in political crisis communication. We are also eager to share with the conference attendees our beautiful city of Innsbruck and maybe even share the odd drink at the department networking event after the presentations are done. The uibk newsroom will update their landing page continuously with the latest conference news: https://www.uibk.ac.at/de/newsroom/2022/1700-politikwissenschaftlerinnen-trafen-sich/

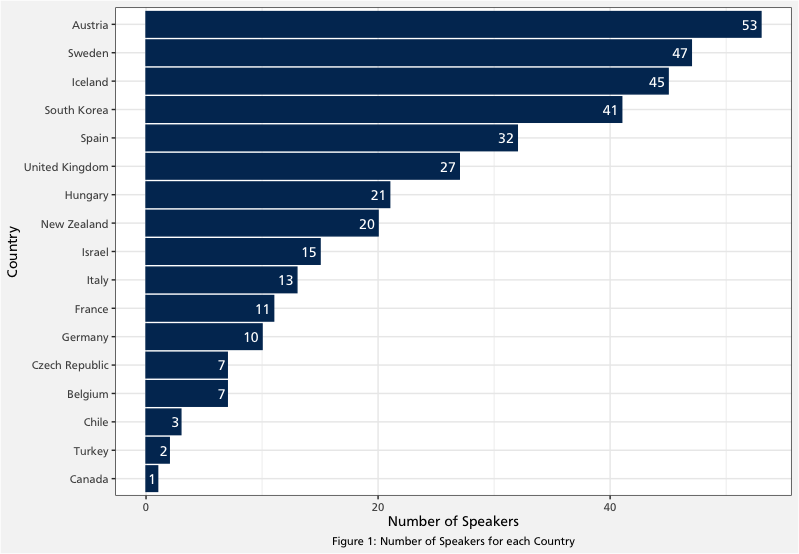

Effective crisis communication depends on many factors, not the least of which is the proverbial messenger – who is speaking to the public?[1] Our sample includes 17 OECD countries, analysed during the initial phase of the pandemic, so naturally, the complete list of speakers is far too long to fully discuss in this blogpost. However, future publications will address the issue in greater detail. For now, we would like to give an overview of the speaker data, specifically the number of different speakers appearing in press conferences, as shown in Figure 1.

Leading the pack – both alphabetically and numerically – is Austria, with over fifty speakers over the course of the initial phase of the pandemic, closely followed by Sweden with 47 speakers, and Iceland with 45 speakers. In stark contrast, Chile banked on all but three people spearheading the government’s effort to communicate through the Covid-19 pandemic – namely President Sebastián Piñera, who appeared alone in the overwhelming majority of press conferences, only being joined by Health Minister Enrique Paris, and medical advisor Dr. María Teresa Valenzuela once to announce the easing of measures. Similarly, Turkey only had two individuals appear in official press conferences – President Erdogan and the country’s Health Minister Dr. Fahrettin Koca – while Canada’s crisis communication strategy consisted solely of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaking to the Canadian public. Clearly, different governments had very different thresholds regarding the number of people involved in public crisis communication.

By Andreas M. Kraxberger and Christian Schwaderer

[1] Seeger, Matthew W. (2006). “Best practices in crisis communication: An expert panel process.” Journal of applied communication research, 34 (3): 232-244.

Before the pandemic turned nearly every aspect of society on its head, press conferences were rather inconspicuous occasions, reported on by the press but rarely actually watched live, never mind by the majority of the population. That, however, changed drastically once governments worldwide realized they would need to frequently communicate to their respective population about an ongoing and rapidly evolving crisis. Quickly, press conferences became a regular occurrence with entire nations tuning in to watch their leaders announce new case numbers, update restrictions and comfort the worried population. This unique focus on press conferences as the main channel of official government crisis communication is also what led us to select press conferences as our unit of analysis.

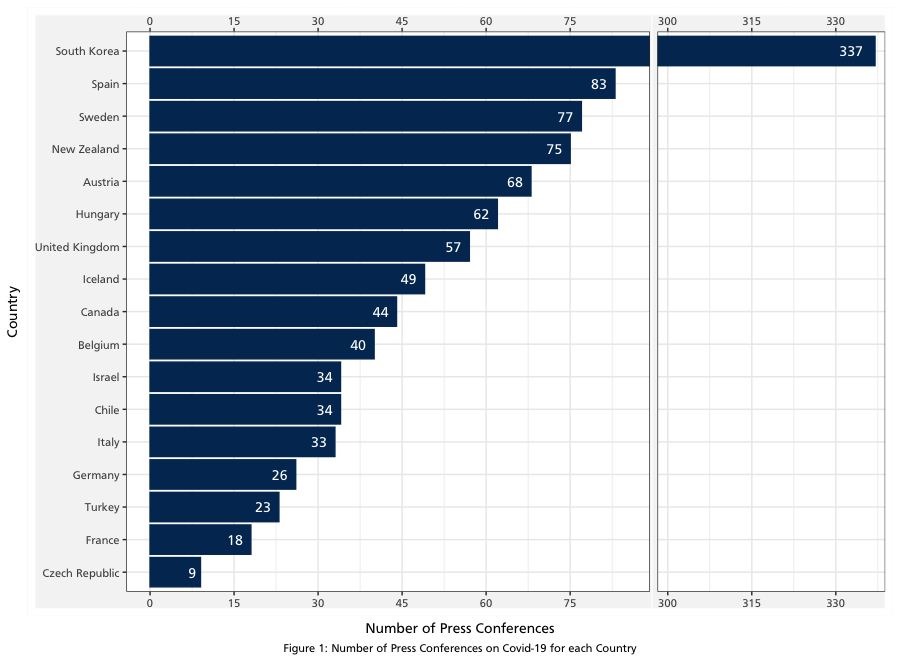

As important as press conferences were in the initial stage of the pandemic, our data shows a considerable variety amongst countries concerning the amount of public appearances, as shown in Figure 1 below.

We would like to point out several interesting data points. First, the absolute dominance of South Korea in terms of numbers. Their government, well versed in crisis communication, and specifically crisis communication during a disease outbreak [1] held at least three press briefings daily to inform the public about various aspects of the ongoing attempts to contain the virus, totalling 337 press conferences within our timeframe of analysis. Second, on the other end of the spectrum, is the Czech Republic. Their grand total of nine press conferences pales in comparison, however, their respective press briefings were on average considerably longer than South Korea’s barrage of public service announcements. Third, three countries – namely Spain, Sweden and New Zealand – are vying for second place in terms of sheer volume of press conferences. While further analysis in the context of our upcoming publications will show significant differences in the overall crisis communication strategies of said countries, and the specific measures put in place have also varied wildly – the pandemic responses of for example Sweden and New Zealand respectively could not be more divergent – it is nonetheless notable that there is a similarity in the pure amount of press conferences held throughout the immediate phase of this pandemic.

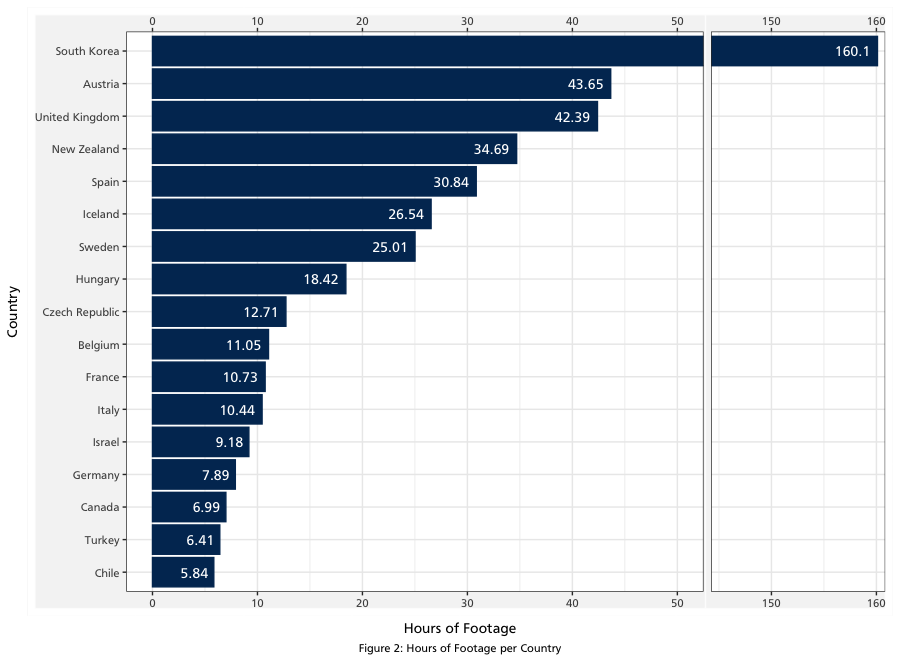

A slightly different picture emerges, however, if one considers the hours of footage derived from the press conferences, as shown in Figure 2. Returning to the aforementioned Czech Republic, it now no longer sits in last place, instead being replaced by Chile with only 5 hours and 50 minutes of accumulated footage. In fact, the Czech Republic now sits comfortably in the mid field, with countries like Turkey, Germany, Canada, Belgium and even Italy, a country famously in dire need of effective crisis communication due to the extraordinarily hard impact Covid-19 had on Italy in the immediate phase of the pandemic, and yet, having broadcast less press conference footage within our time frame of analysis than the Czech Republic did within just nine press conferences.

However, South Korea still reigns supreme, with a total of 160 hours and 6 minutes, the equivalent of almost a full week of continuous broadcasting. Overall we can clearly see that different crisis communication approaches were utilized across the countries in our dataset. Our project will continue to analyse the factors influencing those decisions and thereby further our collective understanding of governmental crisis communication and how it is shaped.

By Andreas M. Kraxberger and Christian Schwaderer

[1] Oh, Myoung-don, Wan Beom Park, Sang-Won Park, Pyoeng Gyun Choe, Ji Hwan Bang, Kyoung-Ho Song, Eu Suk Kim, Hong Bin Kim, and Nam Joong Kim. (2018). "Middle East respiratory syndrome: what we learned from the 2015 outbreak in the Republic of Korea." The Korean journal of internal medicine 33 (2): 233-246.

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has brought about a myriad of challenges for governments worldwide, not least of which was mounting an effective crisis communication strategy during the initial phase of the pandemic. The things we now take for granted, or worse, perceive as annoying and unnecessary – like frequent press conferences, Covid safety campaigns and coordinated government response teams – were an immense logistical challenge for governments to organize whilst dealing with a rapidly evolving situation. Crisis communication literature suggests that this initial phase of the pandemic is crucial if governments hope to achieve successful crisis management in the long term. [1]Our project therefore aims to research this critical time period in depth, examining the broader context in which communication strategies were developed, analysing the strategies of communication that governments and heads of state used in televised press conferences to steer their countries through the immediate phase of the Covid-19 crisis, and publishing our findings to advance understanding of government communication beyond its current scope. Through a combination of three analytic devices – televised press conferences as the most important means of communication, focus on governments and heads of state from 17 OECD countries as the most important political actors, and the immediate phase of the Covid-19 crisis as a distinct timeframe – we will be able to shed a light on the utilized communication strategies as well as any external factors influencing crisis communication.

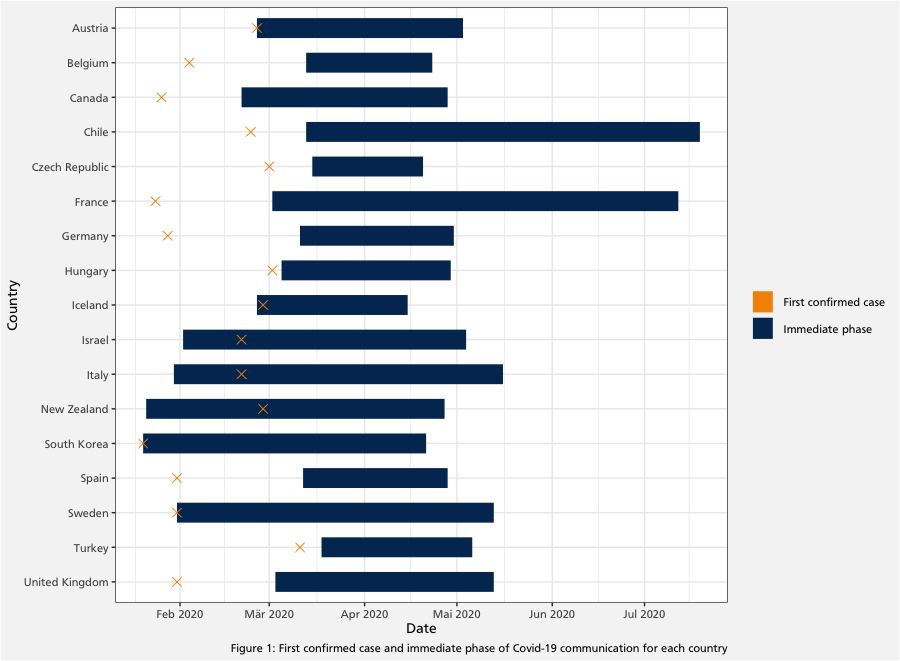

Before we go further into the analysis of concrete communication strategies in future blogposts and upcoming publications, we deem it necessary to outline a broader picture of our dataset, starting with the temporal aspects. Even though the pandemic affected nearly every country around the globe – albeit not equally harsh – the concrete timeline of our sample countries varies considerably (see figure 1 below).

The first government to hold a press conference addressing Covid-19 was South Korea on the 20th of January 2020, only about three weeks after the novel virus was first discovered. In contrast, the last country in our data set to acknowledge the situation was Turkey with a press conference on the 18th of March, making the country a special case in several ways, as will be discussed in future updates. For now, we want to highlight these initial findings. The reasons as to why such a time disparity between Covid-19 government responses exists will be explored further in the context of our research project. Several other results are noteworthy here. First, there is significant variation amongst countries regarding the timing of initial press conferences. Some governments – like New Zealand – started holding regular press briefings prior to their first confirmed case, while others – including Germany, France and Belgium – display a considerable gap between their respective first confirmed case and the first public statement regarding Covid-19.

Yet another notable thing is the varying length of immediate phases in respective countries. We define the immediate phase of crisis communication in a given country as the timespan between the first press conference and the first time measures were eased. Naturally, this largely hinged on the epidemiological situation governments were faced with, like in Chile, where after announcing a relaxation of measures in April, Covid cases spiked drastically, prolonging the immediate phase until mid-July.[2] However, other factors potentially influenced the duration and country-specific approach to crisis communication, an issue which will be discussed in greater detail in upcoming publications.

By Andreas M. Kraxberger and Christian Schwaderer

[1] Claeys, A. S., & Opgenhaffen, M. (2016). Why practitioners do (not) apply crisis communication theory in practice. Journal of Public Relations Research, 28(5-6), 232-247.

[2] Tariq, A., Undurraga, E. A., Laborde, C. C., Vogt-Geisse, K., Luo, R., Rothenberg, R., & Chowell, G. (2021). Transmission dynamics and control of COVID-19 in Chile, March-October, 2020. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 15(1), e0009070.

Funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF)