Roman and Late Antique architecture

Using the Roman city of Aguntum as a case study, Roman Imperial architecture is explored with equal emphasis on residential and public buildings.

City walls

After its discovery by I. Ploner, extensive investigations of the city wall were carried out under the direction of E. Swoboda and F. Miltner. On the eastern side of the town, the wall was uncovered over a total length of approximately 350 meters, revealing several gates and passages. No wall corner was found at either the northern or southern end, leaving it unclear whether the entire city was enclosed by fortifications. The dating of the wall likewise remained controversial in earlier research. During the Innsbruck excavations, it became possible to address this question at selected points.

To the east of the city wall, parts of two buildings were uncovered; large portions of the southern building had already been investigated by E. Swoboda.

Buildings east of the city walls

The parallel alignment of the buildings along the city wall is striking, which is remarkable in that the buildings to the west of the city wall (atrium house) have a different orientation. Due to the orientation of the buildings along the city wall, they could therefore only have been built after the wall. Based on the material found here, construction of the buildings east of the city wall began at the beginning of the 2nd century A.D. In the course of the excavations in the atrium house, it was possible to carry out follow-up investigations directly on the city wall. Of particular note here is a layer of rubbish piled up against the city wall, which contained a great deal of find material from the end of the 1st century AD.

Zweiphasiges Stadttor und östlich davon festgestellte Gebäude

The Innsbruck excavations thus clearly disproved the assumption made by older researchers that the Aguntine city wall was a defensive structure from late antiquity. In the first phase of construction, which can be dated to a period from the granting of city rights under Emperor Claudius to the turn of the first and second centuries AD, there was only a simple 3.5 metre wide passageway at the site of the city gate with two towers that is visible today. The 9.5 metre wide gate was only built in a second construction phase. The buildings to the east of the city wall again provide an indication of the date of this reconstruction. The latest finds from these date to the end of the 2nd century AD, which makes it unlikely that the buildings were used beyond this time. In view of the space required for the newly erected gate complex, it seems plausible that the two buildings located directly to the east in front of the city wall were abandoned in the course of the remodelling. This suggests a date for the remodelling of the gateway no later than the beginning of the 3rd century AD.

Linked to this building history is the question of the hitherto unexplored main gate of the city. As the entire length of the southern section of the city wall has been investigated from the east, the only possible location for the original main gate is north of the gate towers visible today. The intersection of the city wall with the decumanus I sinister is the most likely location - however, geophysical investigations at this point have so far yielded no clear results.

Literature

E. Swoboda, Aguntum. Excavations near Lienz in East Tyrol. 1931-33. ÖJh 29, 1935, 5-102.

F. Miltner, Aguntum. Preliminary report on the excavations 1950-1952, ÖJh.40, 1953, supplement, 93-156.

V. Gassner, Zur Funktion und Datierung der Stadtmauer von Aguntum, Römisches Österreich 13/14, 1985-86, 77-100.

M. Auer, Municipium Claudium Aguntum - Zur Datierungsfrage der Stadtmauer, ÖJh.77, 2008, 7-38.

Atrium house

Research on the atrium house began under F. Miltner and was continued by W. Alzinger. From 1994 onward, excavations were carried out continuously by the Department of Archaeology at the University of Innsbruck. In essence, three building complexes can be distinguished: to the west and south, the kitchen garden; at the center, the actual atrium house; and to the east, a representative wing that earlier research referred to as a private bath.

The eponymous atrium forms the central space of the complex and is characterized by a water basin (impluvium) that collects rainwater through an opening in the roof (compluvium). The water is directed southward and drains into a marble‑lined basin in the garden peristyle.

Atriumhaus – Excavation History

Eastern wing of the Atrium house

According to the finds, the atrium house was built around the mid-1st century AD. This was followed by various modifications to adapt this Mediterranean-style building to southern Alpine weather conditions. Heating systems had to be installed, and rooms reduced in size, to ensure usability during the winter months. The heating installations were supplied with fuel from the kitchen garden to the south and west. Additional rooms were added east of the core atrium house, which itself—visible in its current form—was rebuilt in the 2nd century AD over earlier structures. The defining feature of this so‑called east wing is its large, heated rooms which, although richly decorated with wall paintings, lacked any water-supply installations—refuting the earlier interpretation as a private bath. Rather, it was a representative wing that, with minor alterations, remained in use into Late Antiquity.

Literature

F. Miltner, Aguntum. Vorläufiger Bericht über die Ausgrabungen 1950 -1952, ÖJh 40, 1953, suppl. 93-156.

F. Miltner, Aguntum. Vorläufiger Bericht über die Grabungen in den Jahren 1953 und 1954, ÖJh 42, 1955, suppl. 71-96.

W. Alzinger, Aguntum. Vorläufiger Bericht über die Grabungen in den Jahren 1955 bis 1957, ÖJh.44, 1959 suppl. 75-140.

L. Gomig (Hrsg.), Aguntum. Museum und archäologischer Park (Dölsach 2007).

M. Tschurtschenthaler, Municipium Claudium Aguntum: römischer Wohnluxus in den Alpen, in: L. Dal Ri / St. di Stefano (Hrsg.), Littamum – Una mansio nel Noricum / Eine Mansio in Noricum, BAR Intern. Series 1462 (Oxford 2005) 106-126.

M. Auer, Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Kitchen Residues from the Atrium House, in: G. Nutu / S.-C- Ailincai / C. Micu (Eds.), The man, the river and the sea. Studies in Archaeology and History in honour of Florin Topoleanu on his 65th anniversary (Cluj-Napoca 2017) 327-340.

Macellum

The macellum primarily served as a market for meat, fish, oysters, and other delicacies sourced both locally and from afar. Such delicatessen markets were widespread across the well-connected economy of the Roman Empire. They typically had a rectangular ground plan, though some—especially in central Italy—were circular. Most buildings of this circular type were constructed in the first half of the 2nd century AD, which, based on the small finds, also applies to the macellum of Aguntum.

The plan of the macellum of Aguntum follows a sophisticated architectural concept that was executed with great care. A circular interior with an inner diameter of approximately 17 m is set within a square of about 18.5 m side length (outer dimensions). The innermost core of the building is a decagon with a side length of roughly 3 m and a diameter of about 10 m. The annular zone between the circle and the decagon was divided into nine equal segments by eight radial walls oriented toward the center, together with two rectangular walls and the main entrance on the south.

Traders and customers entered the central decagonal interior from the decumanus maximus via the corridor-like main entrance. Flanking this were eight sales rooms, eacxh with a floor area of around 14 m2. By analogy with other examples, a small sacellum—i.e., a shrine to an as-yet unidentified deity (Mercury?)—may have occupied the ninth room of the same size opposite the entrance.

macellum of Aguntum, condition after excavation

Despite the absence of direct traces, it is reasonable to assume that sales counters stood beside the shop entrances, where transactions actually took place. The customer areas (entrance and decagon) retained parts of a slabbed floor of marble, gneiss, and mica schist. The shops themselves—generally entered only by the merchants—had simple mortar floors with stone substructure. To the south, the macellum was fronted by a covered arcade; to the north, between the macellum and the so‑called "Prunkbau", lay an open square of unknown function measuring around 1000 m2.

Literature

L. Gomig (Hrsg.), Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Das Stadtzentrum (Dölsach 2016).

M. Auer, Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Excavations in the city centre (2006-2015), in: M. Janežič / B. Nadbath / T. Mulh / I. Žižek (Eds.), New Discoveries between the Alps and the Black Sea. Results from Roman Sites in the period between 2005 and 2015. Proceedings of the 1st International Archaeological Conference, Ptuj. 8th and 9th October 2015. In memoriam Iva Mikl Curk (Ljubljana 2018) 93–113.

M. Auer, Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Das macellum, Ager Aguntinus. Historisch-archäologische Forschungen 6 (Wiesbaden 2025).

Merchants' Forum

The merchants' forum was excavated between 2009 and 2025 to the east of the macellum. Covering roughly 3,000 m2, it comprises a central gravelled square measuring about 32×35 m, encircled on all four sides by an approximately 3 m wide porticoe. To the south and east, the covered walkways are flanked by near‑symmetrical rows of six to seven small rooms, each with a floor area of around 15 m2. A similar arrangement existed in the west wing, although later remodelling created larger room units there. Approximately at the center of the room suites, a room of about 75 m2 in the south and one of roughly 45 m2 in the east were added during a 2nd‑century AD remodelling phase. In the same context, two adjacent enlarged rooms were created in the west wing, each equipped with an adjectand, small hypocaust room.

Areal view of the merchants' forum

Rooms in the north of the merchants' forum

The small rooms had simple clay floors and white‑plastered walls. The large central rooms of the first phase were more elaborately appointed, with mortar floors and wall paintings. With few exceptions, the rooms were heated by small niche ovens. Access was generally directly from the corridors; only the enlarged room in the east could be reached solely via the two neighboring rooms.

In the north wing, a room of about 230 m2 in the northeast dominates the layout. West of it lie an L‑shaped room and another large room slightly west of the wing’s center. The northeastern room—measuring approximately 23×10 m—was the largest in the complex. Unlike the southern complex, it had a notably complex history: even before its outer walls were erected, several simple terracing walls and ditches were likely constructed here in connection with the building works. In a second phase, the room assumed its present form and could be entered from the decumanus I sinister via a 3.90 m‑wide entrance. In 2015, three children’s graves were discovered inside the room near this entrance and along the north wall. During the 2nd‑century AD refurbishment, the entrance from the decumanus I sinister was abandoned and replaced by a new opening in the east. A large, only fragmentarily preserved furnace—probably for metalworking—dates to the period after the 3rd‑century AD destructive fire.

West of the large room lies a corridor‑like space in which numerous rock crystals were discovered. Approximately in the center of the north wing was Room R 289, measuring around 45 m2, which in its last attested use served as a storage room. Wherever the room’s contents had not been burned, they were recovered during excavation with a degree of completeness previously unknown at Aguntum. The heterogeneity of the assemblage is striking: vessels of ceramic, bronze, and glass; bronze handles from wooden caskets; tokens; stone weights; rock crystals; and various items of jewelry. Particularly noteworthy are beads for producing blue pigment (Egyptian blue) and pumice stones used for smoothing wood and other materials. Near the north wall, eight iron hub rings were found. West of the room were several iron hoops from two barrel‑like vessels; one barrel was filled with grain that was carbonized in the destructive fire.

Finds from various deep cuts and early construction horizons indicate that the merchants' forum was built around the mid‑1st century AD. In the 3rd century, the building fell victim to a fire, leading to its widespread abandonment. Late Antique reuses are attested in the southwestern entrance area, the central courtyard, and the northern part of the complex.

Literature

L. Gomig (Hrsg.), Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Das Stadtzentrum (Dölsach 2016).

M. Auer, Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Excavations in the city centre (2006-2015), in: M. Janežič / B. Nadbath / T. Mulh / I. Žižek (Eds.), New Discoveries between the Alps and the Black Sea. Results from Roman Sites in the period between 2005 and 2015. Proceedings of the 1st International Archaeological Conference, Ptuj. 8th and 9th October 2015. In memoriam Iva Mikl Curk (Ljubljana 2018), 93–113.

M. Auer / H. Stadler (Hrsg.), Von Aguntum zum Alkuser See. Zur römischen Geschichte der Siedlungskammer Osttirol, Ager Aguntinus. Historisch-archäologische Forschungen 1 (Wiesbaden 2018).

M. Auer,Municipium Claudium Aguntum, in: J. Horvat, St. Groh, K. Strobel, M. Belak (Hrsg.), Roman Urban Landscape. Towns and minor settlements form Aquileia to the Danube, Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 47 (Ljubljana 2024) 243-268.

Ch. Angerer / M. Auer / J. Rabitsch, Where East meets West. Mediterranean and northwestern imports in Aguntum, Noricum. In: Ch. Viegas (Hrsg.), Catarina: Rei Cretariae Romanae Fautorum: Acta 48, (Oxford 2024) 453 - 462.

G. Degenhart / J. Heinemann / P. Tropper/ A. Rodler-Rorbo / B. Zerobin / M. Auer / G. Goldenberg, Mineralogical and Micro-Computer Tomographic (μCT) Texture Investigations of Egyptian Blue Spheres (Aguntum, East Tyrol; Retznei and Wagna, Flavia Solva, South Styria), Minerals 15/3, 2025 No. 302

Craftsmen's quarter

The areas of the ancient city known as the “craftsmen’s and residential quarters” were largely excavated between the 1960s and 1980s. Due to repeated restoration, the individual buildings can no longer be clearly identified on site today. Most structures were likely simple dwellings, typically comprising an open courtyard combined with one or more roofed rooms on the ground floor. These excavations were also re‑evaluated as part of the redesign of the archaeological park. The analysis of the finds from Insula C, carried out as a master’s thesis, is nearing completion.

Insula C during the excavation in 2020

Literature

G. Langmann, Bericht über die Grabungskampagnen 1958 und 1959 in Aguntum, Osttirol, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts 49, 1968/71,143-176.

G. Luger, Der Raumkomplex 'Weggrabung Nord' von Aguntum und die in diesem Bereich gefundene grobtonige Keramik (unpublished dissertation University of Vienna 1989).

Thermae

The thermae of Aguntum were archaeologically investigated in the 1960s and 1970s. Several construction phases were identified, though they were never published in detail. The most comprehensive synthesis of the evidence is found in Silvia Schoitsch’s PhD. Together with the original plans from the 1970s, it indicates that the earliest bath complex—likely dating to the Tiberian‑Claudian period—finds good parallels at Magdalensberg as well as at Herculaneum and Pompeii. Subsequent remodeling reconfigured the complex into the imperial “row type.” A more precise characterization of the building phases will only be possible by combining the reassessment of older excavations with targeted re‑excavations in the bath area. Re‑examination of the bath complex is scheduled to begin in the 2026 excavation season.

Areal view of the thermae

Literature

S. Schoitsch, Kleinfunde aus der Therme Aguntums (unpublished dissertation, Vienna 1976).

M. Auer / M. Tschurtschenthaler , Municipium Claudium Aguntum - Die frühen Befunde, in: U. Lohner-Urban / P. Scherrer (eds.), Der obere Donauraum 50 v. bis 50 n. Chr., Region im Umbruch Band 10 (Berlin 2015) 337-349.

Suburb

The buildings in the suburb excavated by Erich Sowboda in the 1930s require thorough reassessment, as do the craftsmen’s quarter and the thermal baths. The finds from Sowboda’s excavations are now housed in museum Schloss Bruck (Lienz); unfortunately, no documentation of the contexts has survived. What is certain is that the area east of the city along the main roads was also densely built up, and, based on current knowledge, no necropoleis can be assumed up to approximately 200 meters east of the city wall.

Excavation area in the suburbs during the 1930ies

Literature

E. Swoboda, Aguntum. Ausgrabungen bei Lienz in Osttirol. 1931-33, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts 29, 1935, Beiblatt, 5-102.

Municipium Claudium Aguntum in late antiquity

Aguntum’s townscape changed markedly in Late Antiquity. The city center lost its original role as a market and assembly space. Former public buildings were converted into simple dwellings and workshops, where the Y‑shaped tubular heating systems widely used in the Eastern Alps during Late Antiquity are frequently attested. This heating system was also installed in the eastern wing of the atrium house, but there it served a large hall whose material assemblage differs significantly from the simpler dwellings in the late antique city center.

Kanalheizung im Bereich des Forums (Raum 283)

The thermae appear to have remained in use until at least the 4th century AD, whereas the macellum was abandoned after the 3rd‑century AD fire. Various installations indicate that the ruins were repurposed for simple dwellings. In the southern portico in front of the macellum, a furnace for bronze working was installed, as evidenced by several casting drops and a semi‑finished belt‑tongue. The transformation of the city in Late Antiquity was the focus of a research project by Dr. Veronika Sossau, funded by the Tyrolean Science Fund (TWF), which produced the first systematic synthesis of all relevant evidence.

Literature

M. Auer, Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Keramik als Indikator für spätantike Sozialstruktur, RCRF Acta 44, 2016, 453-458.

M. Auer / H. Stadler (Hrsg.), Von Aguntum zum Alkuser See. Zur römischen Geschichte der Siedlungskammer Osttirol, Ager Aguntinus. Historisch-archäologische Forschungen 1 (Wiesbaden 2018).

M. Auer / V. Sossau / S. Deschler-Erb, The periphery of the Mediterranean – Aguntum (Southwestern Noricum) in Late Antiquity, in: I. Borzić / E. Cirelli, K. Jeninčić Vučković / A. Konestra / I. Ožanić Roguljić (Eds.), TRADE – Transformations of Adriatic Europe. 2nd to 9th century AD (Oxford 2023) 78–86.

M. Auer, Municipium Claudium Aguntum. Das macellum, Ager Aguntinus. Historisch-archäologische Forschungen 6 (Wiesbaden 2025).

Early Christian church

Numerous sarcophagus burials were found in the vicinity of the church, most of which had already been removed by local farmers in the 19th century. On the basis of these finds, R. Egger conducted excavations in 1912–1913, which revealed an early Christian church built over a predecessor from the Imperial period. The trench had to be backfilled in 1913, and the site has not yet been re‑examined. Given the church surrounded by numerous sarcophagi, Egger interpreted the building as a “cemetery church.”

Literature

A.B. Mayer / A. Unterforcher, Die Römerstadt Agunt bei Lienz in Tirol. Eine Vorarbeit zu ihrer Ausgrabung (1908).

R. Egger, Ausgrabungen in Noricum 1912/13, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts 17, 1914, Beiblatt, 5-16.

M. Auer / H. Stadler (Hrsg.), Von Aguntum zum Alkuser See. Zur römischen Geschichte der Siedlungskammer Osttirol, Ager Aguntinus. Historisch-archäologische Forschungen 1 (Wiesbaden 2018).

F. M. Müller, Die Ausgrabungen an der sogenannten "Friedhofskirche" von Aguntum 1912 im Spiegel archivalischer Quellen, in: M. Auer / G. Grabherr, Frühes Christentum im Archäologischen Befund, Ager Aguntinus. Historisch-archäologische Forschungen 8 (Wiesbanden 2025) 61-82.

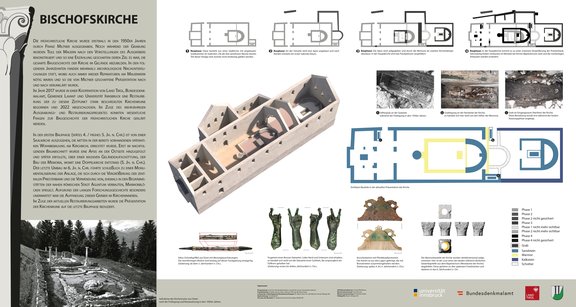

The "Bishop's Church" of Lavant

The church building was uncovered by Franz Miltner in the 1950s. He exposed the basic layout of the entire complex within just a few weeks, which, from today’s perspective, resulted in incomplete documentation and left several questions about the building’s history unresolved. What is certain is that the church was erected over a leveling layer containing finds from the 3rd century AD. The complex comprises two main parts: the “parish church,” which Miltner interpreted as a “bishop’s church,” and a memorial church (memoria) added later as an eastern extension to house the relics of the martyr venerated here. The memoria’s reliquary is well preserved; although Miltner initially interpreted it as a baptistery, it can clearly be identified as a reliquary today. The actual baptistery lies behind the narthex at the opposite, western end of the bishop’s church.

Investigations conducted between 2017 and 2022 largely clarified the construction sequence. The double church developed from an original hall church, later extended by an apse—probably as a memorial chapel—and finally transformed into a double church. In its final phase, the church consists of: baptistery – narthex – parish church – memoria. A subsequent enlargement did not alter this basic sequence but monumentalized the complex, evident especially in the expanded clergy bench in the parish church and the extensive use of marble. Excavations from 2022 onward focused on the church’s immediate surroundings, and during the 2025 campaign a burial ground adjacent to the baptistery was also identified.

Overwiew on the "Bishops church" of Lavant

Overwiew on the "Bishops church" of Lavant

Literature

F. Miltner, Die Ausgrabungen in Lavant/Osttirol. Zweiter vorläufiger Bericht, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts 40, 1953, Beiblatt, 15-92.

F. Miltner, Die Grabungen auf dem Kirchbichl von Lavant/Osttirol. Dritter vorläufiger Bericht, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts 41, 1954, Beiblatt, 43-84.

F. Miltner, Die Grabungen auf dem Kirchbichl von Lavant/Osttirol. Vierter vorläufiger Bericht, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts 43, 1956-58, Beiblatt, 89-124.

M. Auer / J. Rabitsch / S. Deschler-Erb, Worauf Christen bauen - Schaufenster in das 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. unter einer frühchristlichen Kirche in Lavant, Osttirol, in: M. Kohle / P. Trebsche / J. Wallner / S.-J. Wittmann u.a. (Hrsg.), Die Alpen im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Beiträge der internationalen Tagung der AG Eisenzeit in Innsbruck 2023. Innsbruck Archäologien Band 1 (Innsbruck 2025) 259-273.

P. Bayer / St. Karl, Vom Grabbezirk in die Kirche. Bauteile von lisenengegliederten Umfassungsmauern in der sog. Bischofskirche am Lavanter Kirchbichl, in: M. Auer / G. Grabherr, Frühes Christentum im Archäologischen Befund, Ager Aguntinus 8, Historisch-Archäologische Forschungen (Wiesbaden 2025) 47-60.

M. Auer, Der Baubefund der "Bischofskirche" von Lavant - erste Ergebnisse einer Neubewertung, in: M. Auer / G. Grabherr, Frühes Christentum im Archäologischen Befund, Ager Aguntinus 8, Historisch-Archäologische Forschungen (Wiesbaden 2025) 83-102.

J. E. Rabitsch, Die sog. Bischofskirche von Lavant (Bez. Lienz/A). Fundmaterial und Baudatierung, in: M. Auer / G. Grabherr, Frühes Christentum im Archäologischen Befund, Ager Aguntinus 8, Historisch-Archäologische Forschungen (Wiesbaden 2025) 103-126.

L. C. Formato, Die marmornen Bauteile des nördlichen, frühchristlichen Kirchenkomplexes auf dem Kirchbichl von Lavant (Komplex H) - Neubearbeitung und aktuelle Datierungsansätze, in: M. Auer / G. Grabherr, Frühes Christentum im Archäologischen Befund, Ager Aguntinus 8, Historisch-Archäologische Forschungen (Wiesbaden 2025) 127-139.