European Slaves:

Christians in African

Pirate Encounters

News

Lecture “Piraterie, Korsarentum und Sklaverei: Der frühneuzeitliche Kaperkrieg auf dem Mittelmeer” at the Volkshochschule Zürich on May 16, 2023.

Book talk of Barbary Captives: An Anthology of Early Modern Slave Memoirs by Europeans in North Africa at the Columbia Global Centers Tunis on January 6, 2023.

Radio feature

"Versklavt im Mittelmeer – Als Christen und Moslems sich jagten," radioWissen, Bayern 2, September 12, 2022.

Review of Barbary Captives: An Anthology of Early Modern Slave Memoirs by Europeans in North Africa in Goodreads.

Newspaper article

“Vom Sklaven zum Bestsellerautor,” Die Presse, July 23, 2022.

Publication of Barbary Captives: An Anthology of Early Modern Slave Memoirs by Europeans in North Africa by Columbia University Press.

Review of Verschleppt, Verkauft, Versklavt: Deutschsprachige Sklavenberichte aus Nordafrika (1550–1800). Edition und Kommentar in Monatshefte.

Review of Mediterranean Slavery and World Literature: Captivity Genres from Cervantes to Rousseau in sehepunkte.

Review of Piracy and Captivity in the Mediterranean: 1550–1810 in sehepunkte.

Review of Verschleppt, Verkauft, Versklavt: Deutschsprachige Sklavenberichte aus Nordafrika (1550–1800). Edition und Kommentar in sehepunkte.

Review of Piraten und Sklaven im Mittelmeer: Eine Ausstellung von Schloss Ambras Innsbruck und der Universität Innsbruck in sehepunkte.

Review of Verschleppt, Verkauft, Versklavt: Deutschsprachige Sklavenberichte aus Nordafrika (1550–1800) in Historische Zeitschrift.

Review of Verschleppt, Verkauft, Versklavt: Deutschsprachige Sklavenberichte aus Nordafrika (1550–1800) in H-Soz-Kult.

Online article

"Ein weißer Sklave macht Karriere," RP Online, November 13, 2020, online.

Radio feature

"Diagonal zum Thema: Sklaverei," Ö1, February 29, 2020.

"Das Inhaltsverzeichnis," 4:28 min.

"Deutschsprachige Sklavenberichte aus Nordafrika," 5:01 min.

Online article

"Vormoderne Sklaverei am Mittelmeer", science.ORF.at, December 6, 2019, online.

Newspaper article

"Piraten lockten 50.000 Besucher nach Ambras", Tiroler Tagezeitung, September 11, 2019.

Online article

Piraterie und Sklaverei: Auf Menschenjagd im Mittelmeer, Der Standard, July 2, 2019, online.

Newspaper article

"Wie ein Tiroler Bauer von Piraten versklavt wurde", Tiroler Tageszeitung Magazin, July 15, 2018.

Newspaper article

"Menschenhandel im Mittelmeerraum", Die Presse, June 9, 2018.

Lecture

Robert Spindler (Innsbruck), "Renegados: Converted Christians in British Barbary Captivity Narratives", International Symposium Buccaneers, Corsairs, Pirates and Privateers: Connecting the Early Modern Seas, Bielefeld University, 13.04.2018.

Lecture

Robert Spindler (Innsbruck), "Three Early Modern Barbary Captivity Narratives in the German Language and their Portrayal of Islam", Mediterranean Collaborative, Consortium for the Study of the Premodern World at the University of Minnesota, 08.11.2017.

Lecture

Robert Spindler (Innsbruck), "Masters, Agusins and Renegados: Portrayals of Muslims in Early Modern Barbary Captivity Narratives from Germany and Austria", SAGES Program, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, 04.11.2017.

Newspaper article

"Auf zum Entern!", Der Standard.

Lecture

Robert Spindler (Innsbruck), "Merckwürdige Lebens- und Reisebeschreibung: Der Bericht des Johann Michael Kühn", Erzählen zwischen Fakt und Fiktion (workshop), Innsbruck, 23.02.2017.

Article

German article about our conference on "Piracy and Captivity in the Mediterranean: 1530-1810" in Innsbruck.

Newspaper article

"Als christlicher Gefangener unter Piraten", Der Standard.

Contact us:

Mario Klarer

Principal investigator

Telephone:

+43 512 507 4172

Email:

mario.klarer@uibk.ac.at

Mail:

Institut für Amerikastudien

Universität Innsbruck

Innrain 52d

6020 Innsbruck

AUSTRIA

Supported by a grant from the

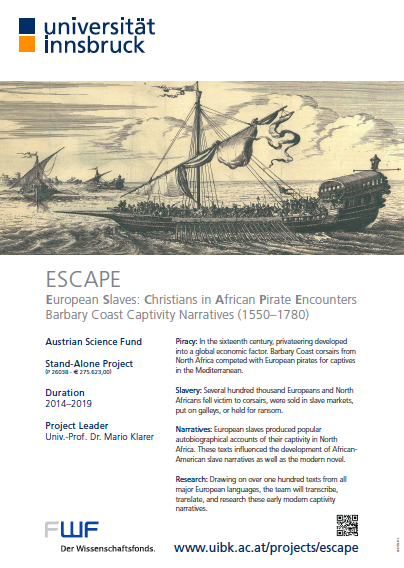

ESCAPE – European Slaves: Christians in African Pirate Encounters

Barbary Coast Captivity Narratives (1550–1780)

Funding organization: Austrian Science Fund (FWF)

Stand-Alone project: P 26038-G – €275,623.95

Project duration: 2014–2019

Principal investigator: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Mario Klarer

The research project focuses on early modern—that is, mostly sixteenth-, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century—survivor narratives by Europeans and Americans who were enslaved on North Africa’s Barbary Coast. Centerpiece of the research effort is an anthology of shorter unedited slave or captivity narratives. Unlike previous research the project primarily focuses on survivor narratives in the English and German language from a literary perspective. These memoirs will be treated as an independent narrative text type or genre, which shares features of the modern novel but predates it by more than a century.

Narratives

Almost all Muslim and Christian regions or towns that were to some degree involved in Mediterranean trade in the early modern era had to cope with the problem of piracy, with corsairs capturing not only trading goods, but also enslaving members of their communities. On the European side, several hundred thousand Christians are believed to have been enslaved between 1530 and 1800 by pirates from Morocco and the Barbary or Berber Coast, the North African Mediterranean sea border with territories of what is now Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria. Large sums of money had to be mobilized in order to return citizens safely to their native towns. Exact numbers of Muslim slaves in Europe are very difficult to determine, mainly because unlike a many former Christian slaves, not a lot of Muslims wrote about their time in captivity.

Many of the European victims of Mediterranean pirates who survived their enslavement later gave or published accounts of their experiences. These narratives form an independent, but in literary studies widely neglected, genre that fulfilled a specific humanitarian as well as political agenda: By describing the hardships, often including gruesome torture and abuse, the survivors painted a picture of terror inflicted on them by the enemy while at the same time depicting stereotypical Otherness that intended to generate hatred towards the captors and compassion for the victims. On a personal level, these narratives conditioned the sympathetic reader to financially contribute to the ransom efforts of groups or individuals to free hostages. On a communal level, these accounts indirectly asked for far-reaching political or military measures to be taken up by communities or states in order to contain and limit the pirates’ activities. In addition to the obvious utilitarian or altruistic motives, these escape narratives also catered to the sensational lust of a readership not yet accustomed to, but definitely ready for the narrative realism the emerging genre of the novel was soon to provide.

The survivor narratives provided the only, albeit distorted, widely accessible source of knowledge about Islam in Northern Africa in the early modern age. The memoirs are one of the most comprehensive precursors to what Edward Said would identify as Orientalist discourses, all of which stylize the Orient as the West’s cultural Other.