Espionage and diplomacy

A British secret agent in a monk’s habit? “Maurus Alexander Horn or, to use his cover name, Mister Bergström could be described as a predecessor of James Bond”, says Claus Oberhauser from the University of Innsbruck. Horn (1762–1820) adopted a number of roles as a monk, diplomat, secret agent and manuscript trader. The FWF project is currently researching all of Maurus (Alexander) Horn’s identities. The aim is to explain the role he played in the power networks of the period and the amount of leeway he enjoyed in diplomatic-political negotiation processes. The research on his points of view could open up new perspectives on historical events like the French Revolution. “Horn was anything but a marginal figure”, says Oberhauser, head of the FWF project. “From his beginnings as a Benedictine monk and librarian, he rose to become Chargé d’affaires – a representative in inter-state relations – at Regensburg’s Imperial Diet. Based on its diplomatic conferences, the latter can be compared with today’s UN and was the meeting point of Europe’s entire ruling elite.” Horn was so successful in asserting British interests there that, with the help of Pope Pius VII, Napoleon himself engineered his withdrawal from the region in 1805. “The consideration of Horn’s activities in the context of European diplomatic history often ends here. Our sources indicate, however, that individual actors like Horn also influenced the course of history from the underground realm of espionage during the Napoleonic period”, notes Oberhauser.

From diplomat to secret agent

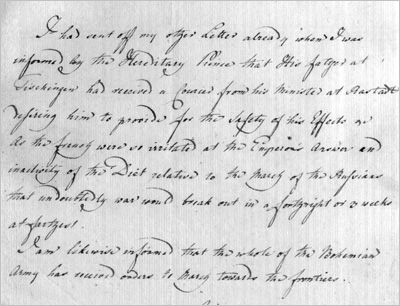

Horn’s career as a secret agent is now being examined in detail for the first time in the context of the three-year FWF project “Diplomacy from the underground. The remarkable career of Alexander Horn”. “Horn was, in fact, involved in trading secret information for the British crown in Linz, Vienna, Prague, Znaim and Frankfurt for around 15 years. His workload was ambitious. He provided two to three written reports to the British Foreign Office every week. A total of around 900 such dispatches exist covering the period 1805 to 1811″, says Oberhauser. The project is analysing the political contexts in which Horn’s meticulous records were used. Horn also played a role in the Alpenbund, a Tyrolean resistance movement against Napoleon at the time, and as a go-between in obtaining financial support for Andreas Hofer’s Tyrolean Uprising from the British.

Social networking

A skilled and successful networker, Horn obtained his information through his dynamic correspondence with other diplomats, politicians and decision-makers. “The private correspondence will play an important role in the project”, says Oberhauser. One important starting point, for example, is the exchange of letters with British nobleman and politician Lord Spencer. The latter supported Horn in his endeavours and he, in turn, obtained rare books, prints and manuscripts from monastery holdings for Lord Spencer.

The cultural history of espionage

The FWF project also establishes a link with current events in that it explores the amount of leeway available to individual actors, who – then as today – often played and play a double role in the diplomatic service and field of espionage. “The communication between these actors also indicates the networks that existed between them and reflects the correspondents’ perceptions of contemporary events. The revealing nature of such correspondence has also been demonstrated, not least, by Wikileaks publications and the current NSA scandal”, explains Oberhauser. The project contrasts the belief in a truth or even conspiracy behind official policy-making with the interpretation of the written sources: These can reveal how political actors constructed their concepts of truth and value in relation to political and socio-cultural realities in discourse and attempted to legitimise them. In this way, established narratives as habitual views of familiar historical events like the French Revolution or the Tyrolean Uprising and possible mythical and heroic inventions can be scrutinised with a view to establishing a broader perspective.

Personal details

Claus Oberhauser studied historiography, history and German in Innsbruck and carried out extensive research visits to Washington, Vanves/Paris, London and Edinburgh. Together with Niels Grüne, he is spokesman for the “Political Communication” research cluster at the “Cultural Encounters – Cultural Conflicts” interdisciplinary area at the University of Innsbruck.